21. Lauffenburg

First mentioned in 1343

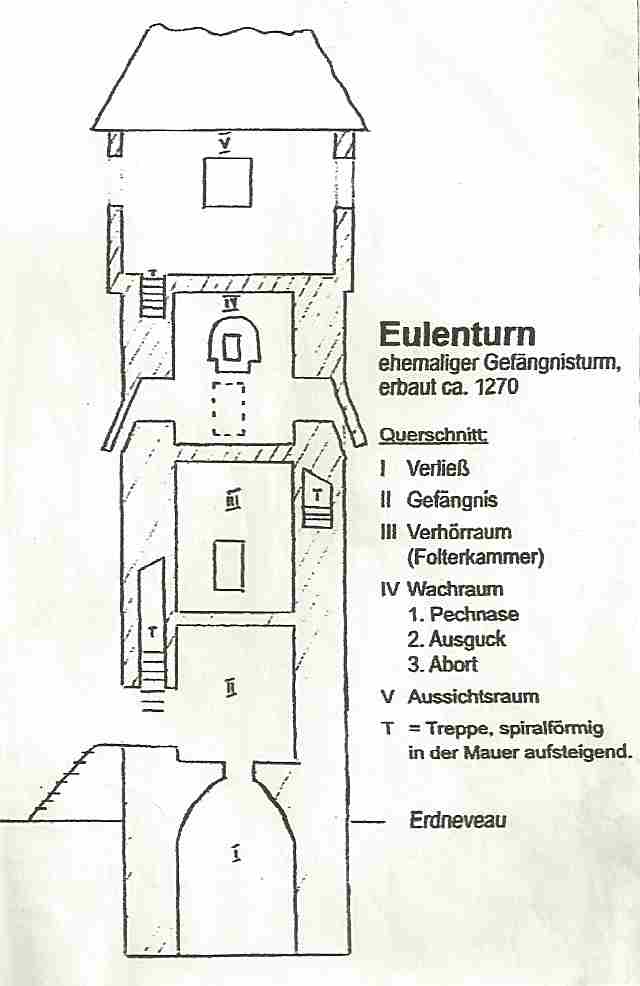

The tower, also called "Eulenturm",

was used as a prison for a long

period. Maintenance and restoration

work from 1981-1982.

The tower, which is also referred to as the “Eulenturm” (owl tower), is the only fully preserved tower of the city fortification. Its age is disputed. It is first mentioned under this name in 1343. The most obvious assumption would be that it was erected as part of the city fortification in the 13th/14th century. Based on the name, another consideration could be assumed. It could refer to the archbishop Bruno von Bretten and Lauffen (1102-1124), who consecrated the Romanesque predecessor church in 1103. In the eventful history of Lauffenburg, the use as a prison and torture tower in the 17th century remains a sad memory. 26 men and women were charged and tortured here, having been accused of witchcraft. The tower was restored from 1981-1982 and furnished as a tower museum.

The Lauffenburg, the building that, along with the collegiate church, defines the silhouette of the town, holds many a secret.

The names the tower has borne over the time of its existence reveal much of its purpose. Eulenturm, Pulverturm, Wachturm, Gefängnisturm, Wehrturm.

The time of the tower's construction is disputed. For the name of the tower leads us to Archbishop Bruno of Bretten and Lauffen (1102-1124), who consecrated the Romanesque predecessor church of the monastery in 1103. The second part of the name "burg", not "turm", is also striking. The residential tower in Bornstraße has also been handed down as Schönecker-Burg. The tower could therefore be the preserved part of a fortified complex built under Bishop Bruno.

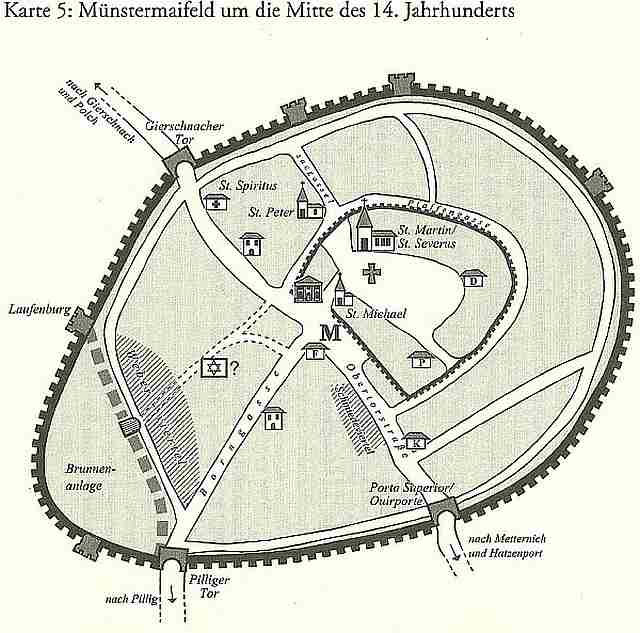

The problem is that we can only document the construction of a town wall under Archbishop Arnold II of Isenburg in 1249. The term "oppidum" for the settlement is also found for the first time for this year. It is difficult to imagine the construction of a tower far from the centre of the settlement around the collegiate church and the institutions important for secular and spiritual life (map) without reference to a town fortification. The only explanation would be the protection of the source of the Severus fountain. In addition, the holders of the bailiwick rights over the monastery and settlement, around 1100 the Palatine Counts of the Rhine, also had the right to fortify the town. It was not until the 13th century that the archbishops succeeded in seizing this right. The name of the tower remains an invitation to further research.

Since the tower was first mentioned in 1343, we can be sure that Balthasar "Laufenburg", who was a prisoner in Lauffenburg in the 15th century and was assumed by Büchel in 1816 to be the patron saint, is out of the question.

Irrespective of the question of when the tower was built, we have known the inner structure of the Lauffenburg since its restoration in 1981-1982.

The climb up the spiral staircase is worthwhile. There are helpful explanations on the individual floors, and the newly added attic offers an impressive view over the city. A particularly sad chapter in the history of this tower is the time of the persecution of witches and witchcraft.

The fate of 26 victims known by name who were held and tortured in Lauffenburg Castle in the 17th century is documented in the exhibition in the tower. According to our chronicler, the tower had six stone gallows facing the town and was therefore also the scene of executions. The last prisoner to be sentenced to death, waiting in the tower for execution in 1761, was Peter Frank. He was executed by the sword. The executioner Peter Wüst had wielded the sword so badly during the execution that he had to leave the town in disgrace.

The last executioner of the town had his small house on the outskirts of the town, leaning against the tower. As a knacker, he had earned the money to build the house by selling horse hides.

Glossary

Knacker

Occupational term for the activity of recycling and disposing of animal carcasses. Another term was Wasenmeister. The Wasen was the lawn that was covered over the carcass. The office of executioner and coverer were often linked. They were considered dishonest professions. Dishonest did not mean fraudulent, but not honourable in the sense of the estates order. The executioner, who was also responsible for the torture, knew human anatomy and with this knowledge also acted as a healer. The profession was often inherited in families. In Münstermaifeld, for example, the Wüst family carried out these activities for over 100 years (1650-1750). The penultimate executioner of this family, Johann Peter Wüst, had to leave the town in disgrace because he had done a bad job with the sword during the execution of Peter Frank in 1761.

Balduin

Archbishop and Elector of Trier (1307-1354). Balduin of the House of Luxembourg, brother of the German king and Roman emperor Henry VII. (1308-1313), was one of the most influential imperial princes in the first half of the 14th century. During his reign, Münstermaifeld became an important base for the territorial policy of the Archbishop of Trier. Thus the completion of the construction of the collegiate church was also a demonstration of Trier's presence vis-à-vis the neighbouring Electorate of Cologne. The reinforcement of the town fortifications confirmed the importance of the Münstermaifeld office in securing the archbishop's rule. The enforcement of the land peace protected the urban development against encroachments by the nobility.

Bruno of Bretten and Lauffen

Archbishop of Trier 1102-1124. In 1103 he consecrated the Romanesque second church of the monastery. In the Investiture Controversy he served the Emperors Henry IV and Henry V with diplomatic missions in negotiations with the Pope.

Arnold II of Isenburg

Archbishop of Trier 1242-1259, he had the city wall with the upper and lower gate built. Obviously the consequence of increased expenditure on fortifications, not only in Münstermaifeld, was a standstill in the construction of the new collegiate church.

Bailiwick (Vogt)

The Vogt, derived from advocatus, gave the necessary protection to the estates that could not or were not allowed to defend themselves. For a long time this included the clergy. The commandment "ecclesiam non sitit sanguinem" also applied to them, i.e. ecclesiastical institutions were not allowed to carry out death and corporal punishment. The task of providing protection by force, if necessary, therefore fell to the nobility, the "warriors". This right of protection, which was also used to build up and expand a territory of its own, was first granted to the Palatine Counts of the Rhine, then to the Counts of Virneburg, until 1285. In that year, Archbishop Heinrich II of Finstingen and Count Heinrich of Virneburg agreed that the Virneburgs would relinquish the bailiwick and the right to fortify the town in return for a payment of 200 marks.

Büchel

On the life of Johann Büchel V. (1754-1842) see Büchel House. He is to be presented here with his work as a chronicler. He held a wide variety of municipal offices. He was therefore very well informed and had access to sources that no longer exist today, dating back to the 16th century. In his biography, which he began in 1828, he lists 58 titles of his manuscripts. Among them are the 12 chronicle volumes that are indispensable for researching the history of Münstermaifeld and the Maifeld. They were written between 1811 and 1828.